How an Italian CFO can explain “living in a leaning tower” to his HQs

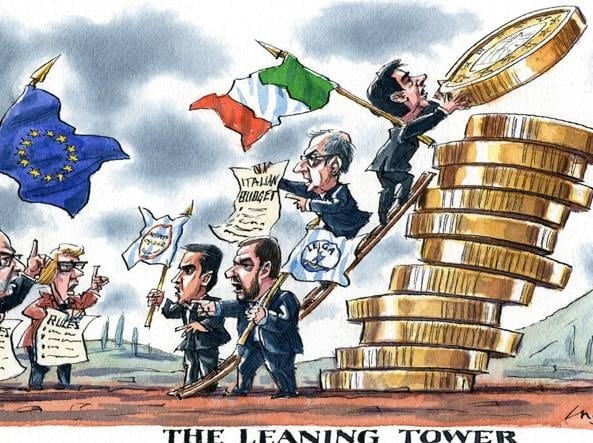

The EU rejected Italy’s draft budget, after the Italian government defied warnings that its plans to increase the government deficit would break EU rules. It was the first time that a member state’s budget has not been endorsed. Italian leaders said that the government would “not give up” on its plans, which include a “universal basic income”, tax cuts and pension reform.

Ingram Pinn’s illustration of the Italian situation published on FT the 26th Oct 2018, I am sure will catch the attention of many colleagues in HQs. The timing of the article is “perfect” as usually November is a month of budget presentation for many multinationals operating in Italy and with this image in front of their eyes, it would be tough for me, as any other CFO based in Italy, to wipe it from their brains.

Too big to let it go (or fail)

The size of the Italian market, usually among the top 8/10 in the world, 3/4 in Europe, is a big guarantee for every CFO, working in the country, that all budget proposals would be carefully listened and taken into consideration. While Italy’ s reputation and ranking as place to do business, sees the country around position 40, when we look at the economic impact, the country is quite in the high ranks. The slow GDP growth of recent years has reduced investments increase as well in the country but, according to a report from ABIE, the Association of Foreign Investors, employment has gone back to the pre crisis level, showing that, generally speaking, the Italian market is “too big to let it go”. Consumption stayed low, but the risk of excessive divesting with consequent failure, makes the negotiation position in the budget preparation stronger.

The Rinascimento

Times when Leonardo, Galileo, Michelangelo and many others were influencing the beautiful years of The Rinascimento are far behind, but their halo effect is still existing at the Budget discussion table. The boom of the 60sties when Italy came out from a poor, agricultural country to the second biggest manufacturer in Europe wafts in the room. What if, all of a sudden another Rinascimento starts and HQs miss the opportunity? The Italian CFO knows it: “Italy has always contrived a way to move out from difficult years” – he says, with a suppressed smile. La Gioconda smiles as well in the minds of the budget discussants and drives the discussion to another positive end.

Creativity and Flexibility

Despite very low percentage of R&D expenses on GDP, Italian scientists obtain a very high number of references in articles written by their peers. There is not, usually, any initiative launched by HQs where Italians are not ready to adopt or just about to do it or even already running it as a best practice. It has been demonstrated by qualified studies that behind the success of our rapid industrialisation after the war, there is an amount of creative, committed, flexible entrepreneurs that “copied” and improved the outputs of more advanced, in terms of industrialisation, countries. That spirit still permeates today corporations based in Italy. Fashion is the symbol of such creativity but in many industries, Italians invented themselves a space in the world economy. Therefore, when the budget meetings turns to “Next Steps”, the Italian CFO starts relaxing: he knows that his local colleagues either have done it already or with very rapid moves, will be ready to adopt every suggestion. The meeting is turning really well.

The leaning Tower

According to Wikipedia, the Leaning Tower of Pisa (Italian: Torre pendente di Pisa) is the campanile, or freestanding bell tower, of the cathedral of the Italian city of Pisa, known worldwide for its unintended tilt.

The tower’s tilt began during construction in the 12th century, caused by an inadequate foundation on ground too soft on one side to properly support the structure’s weight. The tilt increased in the decades before the structure was completed in the 14th century. It gradually increased until the structure was stabilised (and the tilt partially corrected) by efforts in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Italy recorded a government debt equivalent to 131.80 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product in 2017. Government Debt to GDP in Italy averaged 110.97 percent from 1988 until 2017, reaching an all time high of 132 percent in 2016 and a record low of 90.50 percent in 1988. In 2008 before the crisis, it was 100%.

Since 2014 the ratio has stabilised around 130. Has the tilt stopped? Closing his PC, after another positive Budget round, the CFO glance outside the window, no more rain. Good sign.